DRUM! Magazine (March/April 2001)

DRUM! Magazine (March/April 2001)

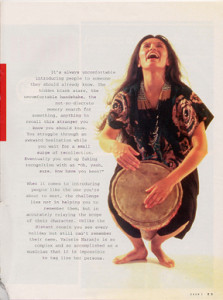

Valerie Naranjo Brings World Rhythms to

Saturday Night Live and Beyond!

From New York, By: Jared Cobb

It’s always uncomfortable introducing people to someone they should already know. The hidden blank stare, the uncomfortable handshake, the not-so-discrete memory search for something, anything to recall this stranger you know you should know. You struggle through an awkward hesitation while you wait for a small surge of recollection. Eventually you end up faking recognition with an “Oh, yeah, sure. How have you been?”

It’s always uncomfortable introducing people to someone they should already know. The hidden blank stare, the uncomfortable handshake, the not-so-discrete memory search for something, anything to recall this stranger you know you should know. You struggle through an awkward hesitation while you wait for a small surge of recollection. Eventually you end up faking recognition with an “Oh, yeah, sure. How have you been?”

When it comes to introducing people like the one you’re about to meet, the challenge lies not in helping you to remember them, but in accurately relaying the scope of their character. Unlike the distant cousin you see every holiday but still can’t remember their name, Valerie Naranjo is so complex and so accomplished as a musician that it is impossible to tag line her persona.

She holds the percussion chair in the Saturday Night Live house band, and you’d think that would be enough, but it’s not. That tag shadows her incredible achievements performing and arranging for the five percussionists in Julie Taymore’s Broadway production of The Lion King. We could take the dirt-to-diva approach and retell the story of how she was working for spare change as a street performer in New York City before she was “discovered” by legendary hand drummer Sanga (Tony Francis). That would contradict her extreme dedication to the study of percussion and its cultural significance and undermine her perseverance through a BFA in Instrumental and Vocal Music at the University of Oklahoma and a master’s degree in Performance and Ethnomusicology at Ithaca College. Or we could take a more cultural angle and delve into her Native American Ute Nation ancestry and the effects that culture has had on her life. Then there’s her abundant success performing with The Phillip Glass Ensemble, her recordings with the gyil master Kakraba Lobi, and don’t forget the milestones she reached as a female drummer in Ghana. But we’ll get to that later.

Like many successful artists, Naranjo’s musical family got her started early in life. “I was about nine when my father gave me a trap set,” she says. “I had a teacher back then who was a great jazz drummer and a tremendous influence on me. Somewhere around the age of 16 I made the leap into more classical percussion. It wasn’t until later that I discovered hand drums.

Like many successful artists, Naranjo’s musical family got her started early in life. “I was about nine when my father gave me a trap set,” she says. “I had a teacher back then who was a great jazz drummer and a tremendous influence on me. Somewhere around the age of 16 I made the leap into more classical percussion. It wasn’t until later that I discovered hand drums.

Naranjo quickly became an advocate of education as she realized the importance of diversity. “I spent several years delving into everything around me,” she says. “I think it’s good to educate yourself on a lot of different things before you start specializing in a specific instrument. That’s the great thing about percussion, if you’re a violinist you’re not required to learn guitar, cello or bass. But to be an effective percussionist that can sit in on diverse gigs, you have to know a lot of different instruments.”

Many percussionists who find they have a natural ability to create music tend to rely on that instinct to build their career. Not Naranjo. She knew it would take total dedication to accomplish her goals. So she spent her early adulthood learning, studying, playing and listening. Upon her graduation from Ithaca, there just happened to be an opening for head of the percussion department at Phillips University. She took the job. “I felt that I needed to do that,” Naranjo explains. “I’ve always enjoyed teaching, and still do, so I thought that I should take a year to experience that.”

From there she packed up her education and played her odds at the New York City music roulette wheel. It wasn’t easy getting started, and she soon found herself on the streets playing marimba for spare change. Until one day a guy named Sanga showed up with his djembe and asked if he could join in. “He stopped by at Columbus Circle one afternoon”, Naranjo remembers. “He introduced himself, pulled his djembe out of its case, and played a great set with me. Sanga then introduced me to the vast world of professional hand drumming”.

Consumed with hand drum fever, Naranjo redirected her studies from mallets to more skinned percussion playing. And she didn’t exactly head down to the corner drum shop and sign up for half-hour lessons. “Sanga was the first hand drum teacher I had and wow, did he have a wonderful sound. All I wanted to do was learn rhythms for accompanying people and he stopped me and said, ‘No, no, slap. Let me hear your slap’. So we started from the very beginning working on basic tones. Then I graduated to running around with him to different drum classes in Queens and Brooklyn. I remember he said to me, ‘Drumming traditionally accompanies movement and movement accompanies drumming, so let’s go.’ And off we went”. Sanga was invaluable to Naranjo’s development as a player. “He showed me how to really watch people and create that dialogue between how they were feeling and what was coming out of my instrument”.

Consumed with hand drum fever, Naranjo redirected her studies from mallets to more skinned percussion playing. And she didn’t exactly head down to the corner drum shop and sign up for half-hour lessons. “Sanga was the first hand drum teacher I had and wow, did he have a wonderful sound. All I wanted to do was learn rhythms for accompanying people and he stopped me and said, ‘No, no, slap. Let me hear your slap’. So we started from the very beginning working on basic tones. Then I graduated to running around with him to different drum classes in Queens and Brooklyn. I remember he said to me, ‘Drumming traditionally accompanies movement and movement accompanies drumming, so let’s go.’ And off we went”. Sanga was invaluable to Naranjo’s development as a player. “He showed me how to really watch people and create that dialogue between how they were feeling and what was coming out of my instrument”.

Like fine scotch, if you want the best hand drumming instruction, you have to get it from the source. So Naranjo’s next adventure took her to Ghana, West Africa, under the direction of such greats as Kofi Missiso, Kakraba Lobi, and Adama Drame. Ghana would become a major part of Naranjo’s life as she visits nearly every year to participate in the harvest festivals. “It’s an awesome place for percussion. Every village has a different specific kind of music and instruments. It’s amazing”. Naranjo has only added to that amazement by using her mastery at the gyil (a type of West African marimba) to establish a chiefly decree that women finally be allowed to play the instrument.

Let’s get back to good old America where saxophonist Lenny Picket was looking to add a percussionist to his impressive list of Saturday Night Live house band members. Guess who got the gig? Naranjo joined the band in 1995 on a temporary basis and immediately had to prove herself to keep the chair. She reflects modestly, “It wasn’t that difficult to earn permanent status in the band. Lenny had already decided that the band would be a lot better with a percussionist. He specifically wanted someone who hadn’t done the regular pop music thing. Well, I’ve never aspired to do that – be it foolish or wise. So when I was on that probationary period they wrote arrangements specifically to highlight my West African style.”

If you think sitting as the percussionist for the SNL house band is a sweet gig, you couldn’t be more right. They perform two to six new tunes for 20 shows a year. At the start of the year they rehearse about 50 new charts for one to four days, depending on the amount of new band members. During a regular shooting week they’ll meet Friday afternoon to perform any necessary prerecords for animated films and other shorts. The commercial-length clips are usually recorded in one take. Saturday is show day and the band will rehearse charts from 11:00 to 1:00 in the afternoon. That’s a quick two hours to run through what can be fairly complicated charts, so you have to have your game on.

If you think sitting as the percussionist for the SNL house band is a sweet gig, you couldn’t be more right. They perform two to six new tunes for 20 shows a year. At the start of the year they rehearse about 50 new charts for one to four days, depending on the amount of new band members. During a regular shooting week they’ll meet Friday afternoon to perform any necessary prerecords for animated films and other shorts. The commercial-length clips are usually recorded in one take. Saturday is show day and the band will rehearse charts from 11:00 to 1:00 in the afternoon. That’s a quick two hours to run through what can be fairly complicated charts, so you have to have your game on.

“We’ll hit each chart once,” explains Naranjo. “If it’s really difficult, we’ll hit it twice. And if the charts are unusually quirky we’ll do two rehearsal takes and then hit it again right before the show.” After a two hour break, the band reassembles for food and makeup, then they warm up the dress rehearsal audience at 7:25. “Our main gig is getting the audience warm. It’s not like Leno where the band is a featured act. At SNL we’re primarily in the background and most of our playing is done I that 20- 25 minutes before we go on the air.”

They run a dress rehearsal of the entire show. Then between 10:00 and 11:00 p.m. the producers will cut roughly one-third of the show, keeping the best two-thirds for the live broadcast. During that hour the band is on break or receives notes on anything that needs polishing. Five minutes before 11:00 they warm up another audience before running the live show at 11:30. “It’s a long day but it’s a nice day and there’s a great vibe on the set,” Naranjo says. “Playing for live television, there could easily be a lot of negative aspects, but it’s a great group of people. The set is always kind of half prepared- like live theater- and it’s always different every show. There’s enough sense of the absurd but at the same time people are writing some slammin’ charts so it’s a serious musical endeavor. To me a Saturday at SNL is a great day because it’s all about being creative and spontaneous.

“I’m extremely fortunate to be playing with a drummer who has really big ears for percussion. Shawn Pelton has trained extensively in classical instrumentation and as a timpanist- and you can hear it. When I switch instruments, he’s right there with me, and that’s a joy. Also, Lenny Picket is a great arranger who really knows how to utilize the talent around him. He has an amazing way of blending funk and traditional marching band music. His compositions are really difficult but according to him they have to sound easy and they have to be accessible to the listener. So he normally won’t give us the charts until we’re at the rehearsal and if it’s too difficult for a musician to get through, it’s too complex for a listener to interpret. Being in one of Lenny’s ensembles means walking into rehearsal and being able to read your face off. It’s a great experience”.

Please tell us there’s something bad about this gig. “It is tough to keep your energy level up,” Naranjo admits. “You sit around for half an hour and then have to play with all your energy, because what really inspires people is playing full out and keeping the energy going. So the biggest challenge is being able to turn on the gas full blast on demand.”

Playing with energy and establishing stamina in her drumming is a philosophy that was reinforced with Naranjo’s arrangement of The Lion King. “When we held auditions for The Lion King, there were some awesome big name musicians trying out, but their biggest pitfall was a lack of stamina,” she says. “On a visit to Ghana, Kakraba Lobi taught me that a big reason hand drummers get tired is that we don’t breathe correctly. We’re not required to breathe air into a horn, so we create some really bad habits. The best players I’ve seen always seem to have a reserve of more, no matter how full out they’re playing. I think that is a result of how they breathe and how they store reserve oxygen.

“Working with dancers taught me that toning up and working out should be a series of circular, never strenuous motions. One of the first things I do in the morning is put on some wrist weights and do some simple circular stretching to get those muscles warm and loose. If I’m planning on a high- volume gig, I’ll take those weights with me and I’ll workout backstage. There’s nothing worse than doing a live gig and feeling like you’re just about to warm up when the gig’s almost over. I also try to get as much rigorous physical activity as possible: hiking, canoeing, skiing, whatever.”

Despite a schedule crammed with some of the best gigs in The City, Naranjo still manages to keep a rather disciplined and admirable practice regime. The Ute in her blood longs to leave the city noise behind and head for the hills, so she normally spends the first part of her week at her home in the Catskills of upstate New York. “I try to spend at least one of those days having a super practice session. I’ll get up around 4:00 in the morning to catch a beautiful view of the sunrise, and I’ll just plow into a new hand drumming technique, or a new piece or whatever. I’ll sit with that as leisurely as I want to. It’s a challenge for a working musician to have their own time to enjoy their own ventures. “I’m also lucky enough to have a studio on the ground floor of my apartment building I live in. I’ll go down there and look at what upcoming gigs I have scheduled and practice accordingly. I’m pretty picky about dividing my time because for any inquisitive mind you can always delve into something and spend many hours on it. So I look ahead at what skills I should have on the front burner.”

Independence is a concept we all aspire to master. Naranjo calls this technique “meta-rhythm” and attributes her success to it. “We have two different arms and sometimes if we combine two different rhythms between those arms and include spaces in between, the sum of the two rhythms can equal more than the addition of one rhythm with the other,” she explains. “There’s a style of gyil playing in Ghana where the concept of polyrhythm and independence is very advanced. For example, they’ll keep a running bass line in 12/8 and start in on top in ? and then continue on top while improvising in another time signature. I get hired for a lot of gigs when they can only use one percussionist and they have a zillion instruments that they want played with some sort of synchronicity. Both in SNL and The Lion King they surrounded me with quite a few instruments and said, ‘Can you keep a cowbell here and put a melodic thing underneath it?’ That’s a challenge for me and it’s something I really enjoy doing.”

Naranjo’s impressive career shows no signs of slowing. She just released a CD on the Lyrichord label called Song of Legaa. It’s a trio comprised of Kakraba Lobi and Barry Olsen with Naranjo on gyil, djembe, lonyana, kakarama and other traditional West African percussion. A second CD from this trio is due out in the early part of next summer. She also plans to join The Phillip Glass ensemble for their world tour this year. You can try to keep up with her by visiting her website at www.mandaramusic.com. So this Saturday night when you sit down to take in another episode of that classic sketch comedy program, you may instinctively miss the days of Belushi, Martin, Murphy, and Murray, but remember to appreciate the talent that’s right in front of you. Valerie Naranjo will be there every week, jamming in the usual whirl of energy and passion that makes her one of the most accomplished percussionists in New York.