My introduction to the Gyil – Percussive Notes 12/98

My introduction to the Gyil

Valerie Dee Naranjo

Percussive Notes 12/98

We live in an age when technological advancement has placed people face to face all over the planet, creating the immediate presence of global misunderstanding amidst the desire for happiness.

We live in an age when technological advancement has placed people face to face all over the planet, creating the immediate presence of global misunderstanding amidst the desire for happiness.

I grew up in the American Southwest. My father is Southern Ute and our family played music together during visits for as long as I can remember. The ideal of music is: It’s fun. It’s available to everyone. It’s a respect worthy way that people fuse their energy and dispel the delusion of separateness.

As a profession, music is as difficult as it is fun. Practically every nation of “folks” has musical spokes pieces – instruments unique to that nation. Alot of those spokes pieces are percussion instruments. Therefore,

being a well-rounded percussionist in today’s popular music scene is a formidable challenge. We have great examples of percussionists who have met that challenge. Max Roach, Tony Williams, Chris Lamb, and Evelyn Glennie to name just four.

Understanding the links between percussion instruments all over the world is not only challenging and fun, it’s necessary. My particular interest is solo marimba.

In a relatively small area of West Africa,the Lobi and Dagara nations have been cultivating solo marimbaphone music for centuries. Words like “polyrhythmic”, and “polymetric” are not in the soloist’s vocabulary, yet in his rendition of traditional tunes, he sets a soulful and spellbinding example of right hand/ left hand independence. Improvising over a jazz standard is a practice he probably has not heard about, yet his format of playing created the concept. By himself, he plays bass, comps chords, and blows over the changes while the drummer (on kuar of gangaa drum) keeps time.

In a relatively small area of West Africa,the Lobi and Dagara nations have been cultivating solo marimbaphone music for centuries. Words like “polyrhythmic”, and “polymetric” are not in the soloist’s vocabulary, yet in his rendition of traditional tunes, he sets a soulful and spellbinding example of right hand/ left hand independence. Improvising over a jazz standard is a practice he probably has not heard about, yet his format of playing created the concept. By himself, he plays bass, comps chords, and blows over the changes while the drummer (on kuar of gangaa drum) keeps time.

The gyil (pronounced JEEL or JEE’lee) is their marimbaphone based on the pentatonic scale. It spans almost three octaves with its 14 keys and is played with two large beaters held between the first and second fingers to allow for a huge dynamic range. Gyils are played in pairs during funerals, and recreationally as a solo instrument accompanied by kuar, a hand drum made from a calabash gourd.

I met African mallet music at the University of Colorado. A Ghanian composition doctoral student, Joseph, directed a weekly workshop on Ewe Drumming for the percussionists in the department. I was taken by his marimba playing. Although Joseph disclaimed “real abilities” as a percussionist, he brought out a different timbre and used the instrument in a unique way. He was directly in touch with a marimba language I’d never heard before. The impression stayed with me.

As a grad student with Gordon Stout, I researched various keyboard transcriptions. I consulted members of the piano department with questions like, “How do you approach Bach’s WTC knowing that Bach never actually wrote for piano?” Purists had a simple answer. “You study harpsichord.” That advice begged a question. “If I am looking for keyboard music as a source of idiomatic marimba transcriptions, why not look to the predecessor of the marimba itself, the dozens of styles of marimbas found all over the African continent?” I was familiar with marimba bands from Zimbabwe, Zambia and Mozambique, and the balafon ensembles found in Cameroonian Catholic churches. “Yet”, I wondered, “Does there exist a style of solo polyphonic marimba music from the African tradition?”

As a grad student with Gordon Stout, I researched various keyboard transcriptions. I consulted members of the piano department with questions like, “How do you approach Bach’s WTC knowing that Bach never actually wrote for piano?” Purists had a simple answer. “You study harpsichord.” That advice begged a question. “If I am looking for keyboard music as a source of idiomatic marimba transcriptions, why not look to the predecessor of the marimba itself, the dozens of styles of marimbas found all over the African continent?” I was familiar with marimba bands from Zimbabwe, Zambia and Mozambique, and the balafon ensembles found in Cameroonian Catholic churches. “Yet”, I wondered, “Does there exist a style of solo polyphonic marimba music from the African tradition?”

I found a recording of Ghanaian master Kakraba Lobi while combing through record shops in Harlem.

I took my first journey to Ghana to seek out Kakraba in Accra, the capital city, and to journey to his homeland – the Upper West of Ghana. In order to find out more about this mysterious instrument and the people who created it. I didn’t find Kakraba (he was in Japan). I was, though, able to stumble nose-first onto the Lobi and Dagara Nations’ largest gyil festival, Kobine.

I traveled from Accra to the Upper West capital Wa, alone (a grueling 18 hours on a crowded state transport bus) and was escorted to Lawra, the home of Kobine, by one of Ghana’s Arts Council officers, Mr. Donzie, who had performed extensively in the United States. “What is your ethnic background?” he asked. “Native American.” “Where did you grow up?” “In Colorado. The town is 120 miles north of Santa Fe.” “Ah Ha!” he exclaimed. “You will like it here. You are just like us here, and our Lawra town is just like your Santa Fe!” “He’s being so kind,” I thought. “Trying to make me feel at home half a globe’s distance away.”

I traveled from Accra to the Upper West capital Wa, alone (a grueling 18 hours on a crowded state transport bus) and was escorted to Lawra, the home of Kobine, by one of Ghana’s Arts Council officers, Mr. Donzie, who had performed extensively in the United States. “What is your ethnic background?” he asked. “Native American.” “Where did you grow up?” “In Colorado. The town is 120 miles north of Santa Fe.” “Ah Ha!” he exclaimed. “You will like it here. You are just like us here, and our Lawra town is just like your Santa Fe!” “He’s being so kind,” I thought. “Trying to make me feel at home half a globe’s distance away.”

He was right. My first impression of Lawra mirrored childhood images of my own home. Reddish dust flew into the air every time a pickup truck drove by (which was infrequent). Most of the houses were mud brick. Older women shucked corn tossing big shallow basketfuls of dry corn into the air which allowed the breeze to blow away the chaff.

Later that morning I was taken to the compound (extended family home) of the master gyil player and gyil builder of the region, Newin Baaru. A polite yet probing interview ensued. Baaru needs to ensure that anyone who wishes to play gyil is truly dedicated to it and is the kind of spirit that can “carry” the music, since to the Dagara, the spirit and intention of the musician can affect either a healing or destructive energy.

I was then given a pair of mallets and a gyil was placed in front of me. I could then show to them the result of five years of struggle and study from recordings without a teacher. I united with my second soul family at that moment. The men whooped. The women and children danced and sang songs that I’d been playing but had never heard sung before.

I was then given a pair of mallets and a gyil was placed in front of me. I could then show to them the result of five years of struggle and study from recordings without a teacher. I united with my second soul family at that moment. The men whooped. The women and children danced and sang songs that I’d been playing but had never heard sung before.

The first lesson, which was with Baaru, began early that evening at the compound of Vida Tenney-Dunia, who took it upon herself to host me. Baaru walked into the yard, set up the gyil, sat behind it and began to play a basic Dagara dance song (yet complicated to me). I expected him to stop at some point and say, “OK you start this way.” No. One learns to play from Baaru (and any other traditional master) by observing, and observing some more. I remember learning stomp songs (Native American recreational songs) that way.

When enough time had passed, he pointed to my left hand with his jaw. “Are you ready?” “Yes.” Without stopping the music, I took over the left hand line, later the right hand line. Within minutes I was exhausted. I stopped playing. He got up, disturbed, picked up the gyil and turned to leave. “Where are you going?” “You stopped.” “Ah, but I didn’t mean to stop for the evening. I just needed to take a break!” “Tek brek?!” he demanded. One of the youngsters translated the American phrase “Take a break.”

“No, no, no, no, no,” he shook his head shamingly. “When you play gyil here you do not Tek Brek! You must be strong, strong!” He left.

“No, no, no, no, no,” he shook his head shamingly. “When you play gyil here you do not Tek Brek! You must be strong, strong!” He left.

Indeed the phrase “Take a break” left my vocabulary. By the next morning I had three teachers: Baaru, Richard Na-Ile, and P.K. Derry. We stopped playing only to eat and for me to meet new friends. I was overwhelmed by the depth of their knowledge and the generosity of their spirit. What did they expect from me? Whatever fee I choose to give, and for me to do my best. Richard explained, “You disrespect the music if you keep it or try to make undue profit from it.”

One thing they knew: in order for me to really understand the gyil, I would need to develop the stamina to participate in the overnight sessions during Kobine where the music is not allowed to stop, and where a gyil player may play for hours at a time. A far cry from my first twenty minute lesson!

Women now Play

News of a new gyil player, a white woman from far away, spread quickly. The Paramount Chief of a territory, according to local tradition, is the final advisor and judge of all events and situations among the people.

Chief Abeifa Karbo III called for me to visit him and his council, a body of elder men who hold positions of leadership and responsibility, who meet most weekdays at 5 PM. I had a friendly interview. The chief asked incisive questions about my intentions, then requested that I return the following day with my instrument.

What an honor to have my teacher Baaru as my accompanist. During my performance the chief got up, alone, and danced. “How kind,” I thought. I didn’t know that chiefs do not dance, and that his action was a strong statement.

Up to this point tradition banned women from even touching a gyil, although no one seemed to actually know why. Chief Karbo, a well-travelled man with a degree in law, harbored a desire for all of his subjects to realize their full potential, especially women, some 65 – 70 percent of the adult population. Already many women in Lawra were heads of businesses, yet had to endure the scorn of older people who were used to seeing women in traditional subservient roles.

The moment that Baaru and I finished, the council members were all talking at once. They were discussing in the Dagara language the fact that, not only was I a gyil player, but a woman and a foreigner at that. “And why don’t our women play, anyway?” As they were exhausting their options, Chief Karbo stood up. A strong figure clad in a fine purple robe, he threw his hands in the air and declared in English, “from now on women will be allowed to play the gyil!”

Kobine

Kobine (pronounced KO’-bee-nay) is a four-day, three night preharvest festival which takes place in Lawra on either the last weekend of September or the first weekend of October. It is considered to be the place to hear the finest gyil players and composers.

The day before the festival’s official opening, a hush of anticipation falls over the town. One by one, music and dance groups arrive, you hear them before you see them, and as they stop in Lawra’s transport yard they jump out of the old flatbed trucks or decrepit busses playing, singing, and wearing their finest traditional dress. In a few hours, Lawra is transformed from a sleepy little village to a noisy colorful, rich display of joy and beauty.

Pito (pronounced PEA’- too) is a homemade millet beer. During Kobine residents’ backyards become huge Pito bars and outdoor food stands serving sumptuous stews and dishes. Merchants set up shop and display their wares. Everything from simple tools to lavish works of art. The sound of gyil is constant.

The first official event of Kobine is the Greeting of the Chief. Each visiting chief and his court musicians travel in a procession to the palace of Lawra’s Chief Karbo where greetings are exchanged. Meanwhile, the public assembles on Lawra’s main road for the Grand Procession to the festival grounds. In an enormous pageant the entire party moves to a song sung by the women. The public takes its place on the west and south sides of the festival field, the chiefs and their courts take their seats on the north side, and the music/ dance groups (at least one to represent each village) continue to parade around the perimeter of the field so that every one can see them “up close”.

After the announcement of Kobine by the Hoori-Hoori Man (an elder musician who uses a calabash flute) an hour of speeches, and the dramatic retelling of the origins of Kobine, the real festival begins. For the next 4 or 5 hours the gyil groups are in official competition. One after another they go onto the field for a designated ten minutes and “show their stuff”. The group is generally, one or two gyil players and 2-6 kuar players. The singers/ dancers, each playing metal shakers bound to the feet and a cast iron clapper in one hand, move in a circle around them.

At dusk, the groups assemble informally and continue, usually all night.

The following afternoon, the competition continues, finalists having been chosen by a panel of judges. As the competition becomes fiercer one experiences a finer and finer display of strength and virtuosity. The “throwing of ashes” in honor of ancestors is the solemn ceremony that closes Kobine on Sunday morning.

Ghana’s Gyil Concert Soloist

I returned to Ghana the following September after receiving a letter from Kakraba inviting me to study with him. Kakraba Lobi is regarded at home and abroad as the nation’s foremost gyil master. Having grown up with the instrument in his family, he perfected his art while still a teenager. A vibrant youthful man in his 50s, Kakraba has taken the art of gyil playing, composing, and improvising to new levels. At times, he improvises both left and right hand lines simultaneously, yet in different times (i.e. 6/8 in the left hand, 4/4 in the right). The music is astounding as if I am watching one man play, yet I am hearing two of them!

Now a well-in-demand concert soloist who performs all over the world. He is a Ghanaian living legend, considered in his homeland to be the world’s gyil spokesperson.

It took an afternoon and a guide to find Kakraba’s main house. After meeting with this great master we set up an appointment.

“Do you wish to learn in the traditional manner?” “Oh, yes, of course,” I replied.

He growled in response. Did I know what I would be in for?

The next morning, we met for the traditional initiation libation, a short ceremony that honors the masters who have passed. In traditional pedagogy it is given that those who have died are still with us, and will assist us if we acknowledge them.

Kakraba chose the space where I would study and placed ed the gyil there. He then broke the seal on a bottle of fine gin, which he had instructed me to bring for the occasion, and poured two drops on each of the four corners of the keyboard. He then poured a drop on each of the beaters and poured a generous helping of gin in two glasses: one for himself and one for me.

I recited a traditional prayer; he did the same. Then it was “down the hatch”.

He immediately began a session on how to “warm the gyil” which is the playing of pirey, introductory phrases that all traditional players do when they first approach an instrument. This music, based on spoken language connects the musician with his/her musical masters, living and dead.

My first teachers avoided this painstaking process. Kakraba began with it. The phrases were lengthy, complicated, and based on a language that I didn’t yet understand. Furthermore, I was very drunk. I had two choices: to embarrass myself by relying on my intellect, or to ask for help from those experienced experts whom we had just prayed to. I did the latter. To my astonishment and to Kakraba’s smiling nod, I began to warm the gyil.

That was the first of many amazing experiences studying with gyil master Kakraba Lobi.

We have recently completed a series of marimba transcriptions of his gyil music in hopes of helping to fill a space in marimba literature for traditional solo music from the African continent.

The Music

Gyil is “the voice of the people” and its range incorporates the vocal range of those who sing with it. The tunes themselves are usually short and repeat a parable or observation.

The study of gyil music provides a key to idiomatic capabilities specific to mallet instruments. For example, marimba beautifully expresses what drum set master Kenwood Dennard has coined “Metadependence”, which occurs when two or more interdependent lines interlock in dialogue between the right and left hand.

The construction and playing of the gyil are regarded as a single art, the masters of which hold a respected post. Although truly mastering the art can take most of a lifetime, all men in a community are expected to be able to play at least a few simple tunes. (Women have also recently begun to play.)

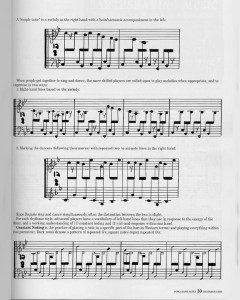

A “simple tune” is a melody in the right hand with a bass/ harmonic accompaniment in the left: (From Darkpe) (Please refer tothe printed article.)

When people get together to sing and dance, the more skilled players are called upon to play melodies when appropriate, and to improvise in two ways:

1.) Right hand lines based on the melody (From Darkpe)

2.) Marking the dancers (following their moves) with repeated 2-6 note lines in the right hand: (From Darkpe)

Since Dagara people sing and dance simultaneously, often the distinction between the two is slight.

The advanced player has for each rhythmic style a vocabulary of left hand lines that he/ she uses in response to the energy of the dance, and has a working understanding of 1.) constant noting and. 2.) call/response within one hand.

Constant Noting is the practice of placing a note in a specific part of the bar (in Western terms) and playing everything within that parameter. (From Darkpe)

Call/ Response within one hand is simply that, with one hand a “call” is played on a specific range of the instrument, its response on another: In the right hand (from Japlek) In the left hand (from Japlek)

These techniques, of course, can be combined in either or both hands simultaneously in a single meter: (From Japlek) Or in two meters at once: (From Darkpe)

Other available techniques are the use of open and “dead” strokes, and the striking of the bar with mallet shaft. In the following section of Kpanlogo (MUSIC EXAMPLE COMING SOON), these techniques create the illusion of two voices within a single line:

(place music example)

The gyil master can improvise using any of the aforementioned, track a dancer, support a singer, change key at will, play for a long period of time with no break – and knows how to construct the instrument. He / she is truly a world class artist.

Conclusion

I was taken to Ghana because of the magic of the gyil. My experiences taught me that this quality in the music is a reflection of the depth and beauty of the people who created it.

In Ghana I’ve never been regarded as a stranger or an outsider, and whenever I’ve taken an opportunity to explain my intentions, my listener becomes my comrade, willing to help my cause.

I am indebted to many: to the people of Lawra, especially Paramount Chief Naa Abeifa Karbo III who made his court available to ensure my comfort, and master musician Baaru; to Kakraba for being so strict yet caring, and for rearranging his busy schedule to accommodate me; to American musician Robert Levin for generous hours of advice; and to all the Ghanaian people, who remind me of something that I learned as a child: Richness of the human spirit coupled with the natural richness of the environment create the most valuable things in life. Great music is one of those things.